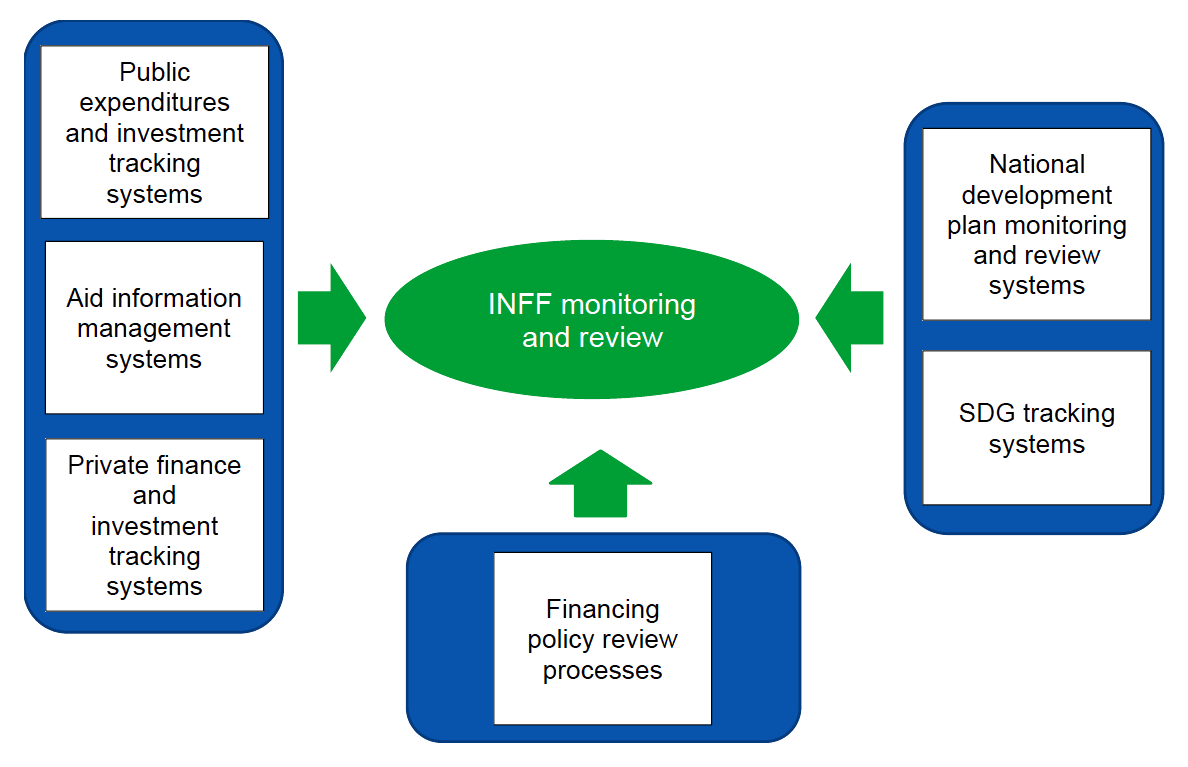

Countries do not need to

start from scratch when it comes to INFF monitoring and review. Existing

monitoring systems, processes and frameworks should be the starting point. Such

systems can be strengthened or expanded, better aligned and made more coherent within

an INFF as necessary. Similar to Building Block 4 Governance and Coordination, the overarching aim should be to streamline efforts,

not to replace or duplicate existing systems nor to establish new systems,

unless there are gaps that need to be filled.

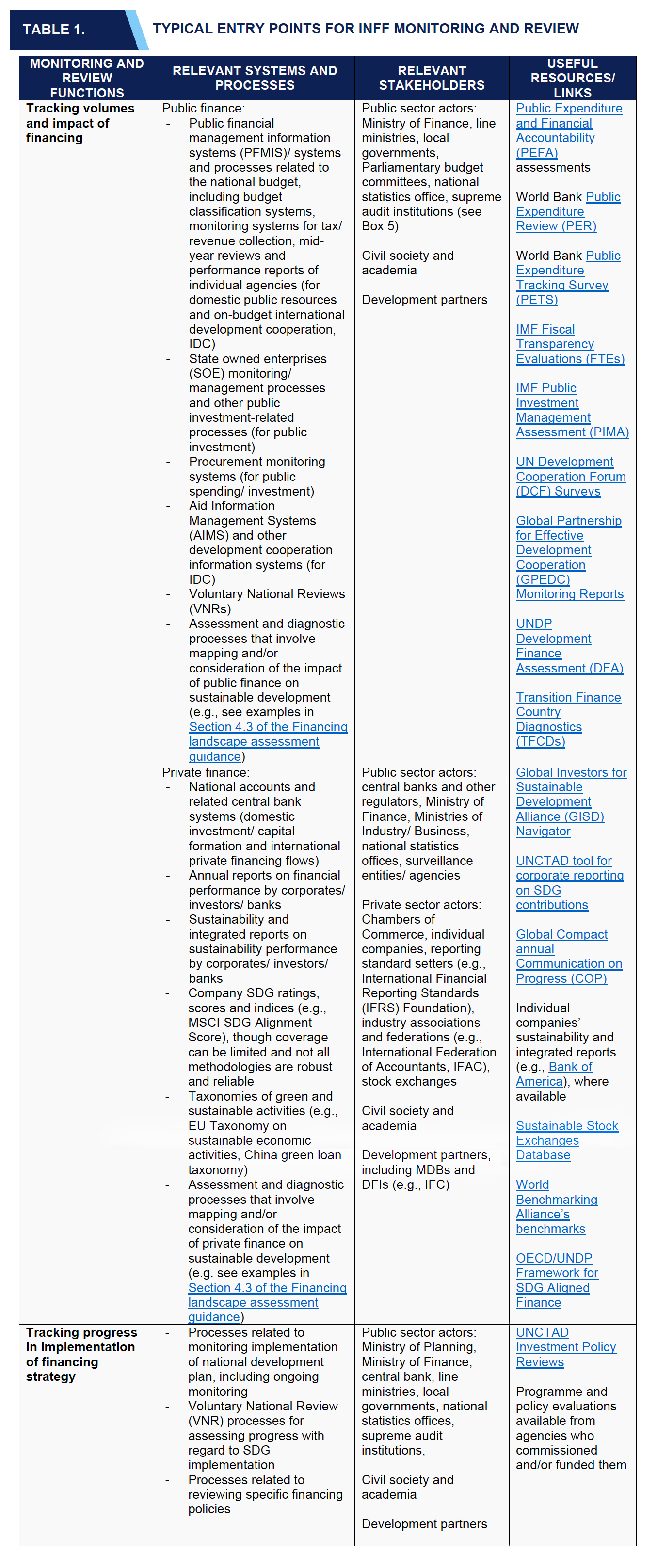

Table 1 illustrates potential

entry points for INFF monitoring and review, as well as relevant stakeholders typically

involved in establishing and maintaining adequate systems. It also includes links

to useful resources and tools that can shed light on existing systems and processes.

(Table 2 in Building Block 1.2 Financing Landscape

Assessment provides an overview of

data sources, which can inform the tracking of volumes of financing).

Overall, if a

well-established system for monitoring implementation of the national

development plan is in place, it could serve as a starting point for INFF

monitoring and review. Similarly, if established processes around Voluntary

National Reviews (VNR) exist, these should also be considered (see Box 4). Data

and statistical strategies and reform processes may constitute another entry

point (see more in Section 5.2, Action Area 3). Existing monitoring systems for

different types of finance (such as national budget tracking systems and review

processes, or private finance reporting initiatives) can act as entry points to

build a more comprehensive system. As further articulated in Section 5, the comprehensiveness

of such a system will differ depending on country contexts, reflecting the

nature of INFFs as a long-term and gradual approach to guide better planning

for, and implementation of, financing policy reforms.

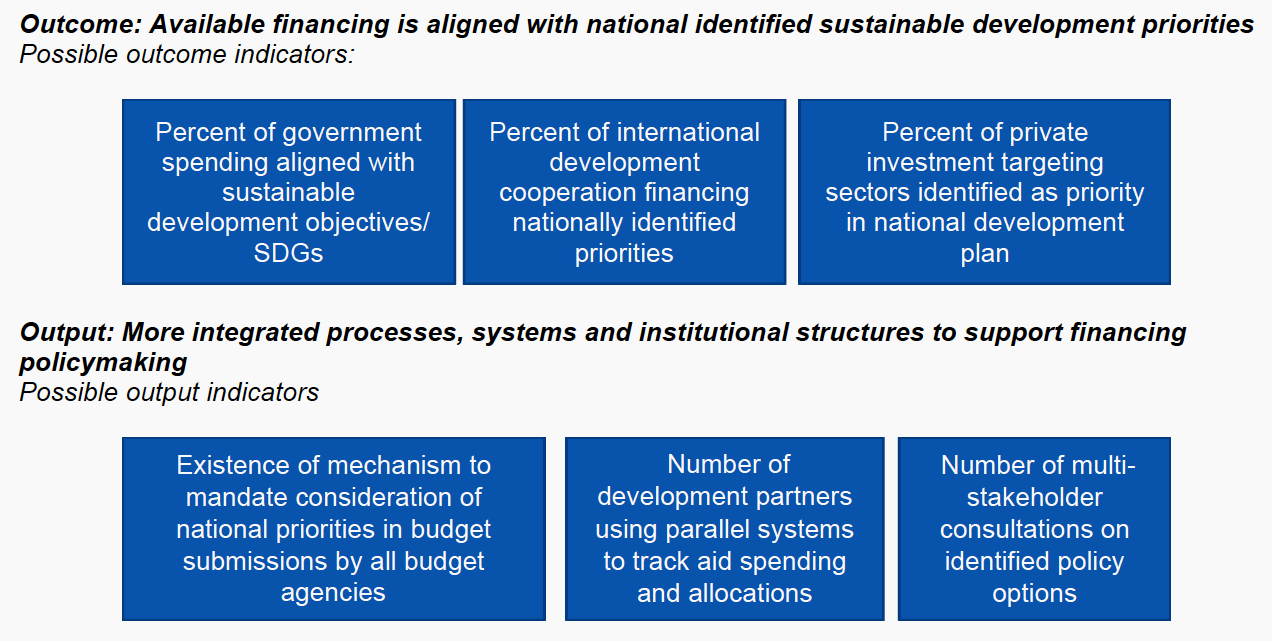

With regard to public finance, monitoring

systems relate to government finance (revenue, spending and investment), as

well as development cooperation. Public financial management information

systems (PFMIS) are typical starting points from the government’s perspective. A

growing number of countries have gender, climate, or SDG budget tagging or

coding systems in place, or are developing them as part of their INFF. Monitoring

systems for government finance are usually developed around the annual budget

process, with both volumes and data on performance indicators reported in

relation to objectives that programmes within each budget agency are expected

to achieve on an annual or multi-year basis. In the budget planning and

formulation stage, and as part of their submissions to the Ministry of Finance,

budget agencies may be required to articulate a narrative around how they will

contribute to identified national priorities or the SDGs, and/or to link their

programmes to specific goals. Data on government revenue may be collected to

various degrees of disaggregation and may be subject to review with regard to

questions of progressivity or inequality. There are also varying practices in

relation to monitoring of tax expenditures, used to shed light on revenue

foregone through tax incentives. Specific monitoring frameworks may also be in place

for major investment projects (e.g., articulated by ministries and other

entities involved in major infrastructure projects) and for state-owned

enterprises, which may have dedicated systems to track their investments and

contributions toward national development.

Monitoring systems for development cooperation and

finance are based on national aid information systems and country results

frameworks. According to 2018 GPEDC monitoring data, 96%

of developing countries have one or more information management systems in

place to collect information on development cooperation. While the quality of

such information varies, it typically includes data on financial commitments,

scheduled and actual disbursements, and in some cases on intended and achieved

results. Data from the 2020 DCF survey shows, however, that less than

half of development cooperation information systems tracked results, off-budget

flows, funding gaps and conditionalities. A results framework to review the

performance and results of international development cooperation was in place in

just over half of respondent countries (56%). Critically, in the context of an

INFF, in only 36% of cases countries and development partners use the same, or

mostly overlapping, results framework, meaning that there are multiple parallel

systems. Furthermore, only half of results indicators from development

partners’ projects are monitored using national statistics and monitoring

systems, according to GPEDC data.

With regard to private finance, the monitoring

and reporting landscape is even more fragmented. On financing flow volumes,

national accounts and related central banks reporting are common systems. In

addition, relevant line ministries (e.g., ministries of business or local

development) may have systems in place to collect and report data on

investments in the country, including in relation to the role of SMEs at the

sub-national level. Beyond volumes, policymakers need data and information on

the impact of private business and investment on economic, environmental, and

social issues to assess the private sector’s contribution to sustainable

development objectives. Meaningful data and information on this remains scarce

though a number of initiatives and innovations are ongoing, with INFFs providing

a platform for enhancing coherence of this increasing wealth of information at

the country level and feeding it into financing policy making processes.

For

example, private sector- or government-led systems for consolidating data on

the contributions of business to sustainable development priorities exist in

some countries (e.g., in the Philippines and in Colombia) and

there is a growing number of companies publishing a sustainability report

(mainly large, listed companies). However, information published is often not

comparable across companies or time, and tends to focus on qualitative indicators rather

than on quantitative data. Companies select the issues they choose to

communicate, as sustainability reporting remains largely voluntary. In

addition, sustainability-related information is generally behind paywalls and

is not in the public domain; policymakers could change this by creating an open

repository for company sustainability data to create more transparency. Companies

also need to adjust their internal systems to track and report data on

environmental and social issues. This might be particularly challenging for

smaller companies with limited resources. Nonetheless, voluntary sustainability

reports can be a starting point. Governments can increase their relevance by

agreeing (including at the global level) on harmonized metrics and indicators

to be used for company disclosure. Countries across a range of development

contexts (e.g., EU, China, Mexico, South Africa, Mongolia, Bangladesh) have

developed or are in the process of developing taxonomies that could enhance reporting

on both volumes and impact of private business and finance. The G20 Sustainable

Finance Working Group (SFWG), established in 2021, is also working on improving

corporate sustainability disclosure and on facilitating the compatibility and

consistency of national approaches regarding sustainable taxonomies. The INFF

process can help consider these national and international efforts in connection

to public finance classification systems.