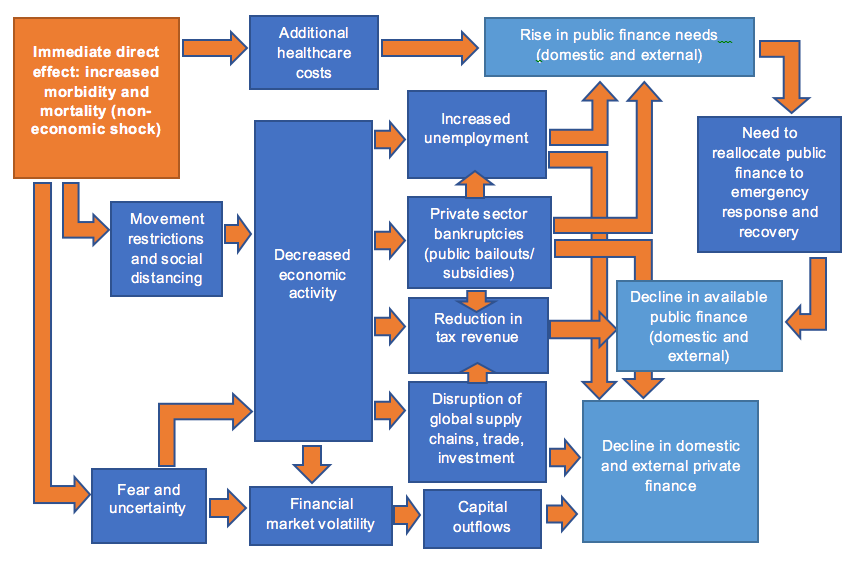

The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored that development must be risk-informed to be sustainable. The initial public health shock and the cascading socio-economic effects triggered by the pandemic are undermining and reversing previous development gains. As shocks, disasters and crises are becoming more frequent, intense, and interconnected, a thorough understanding of a country’s risk landscape is an indispensable element of sustainable development efforts.

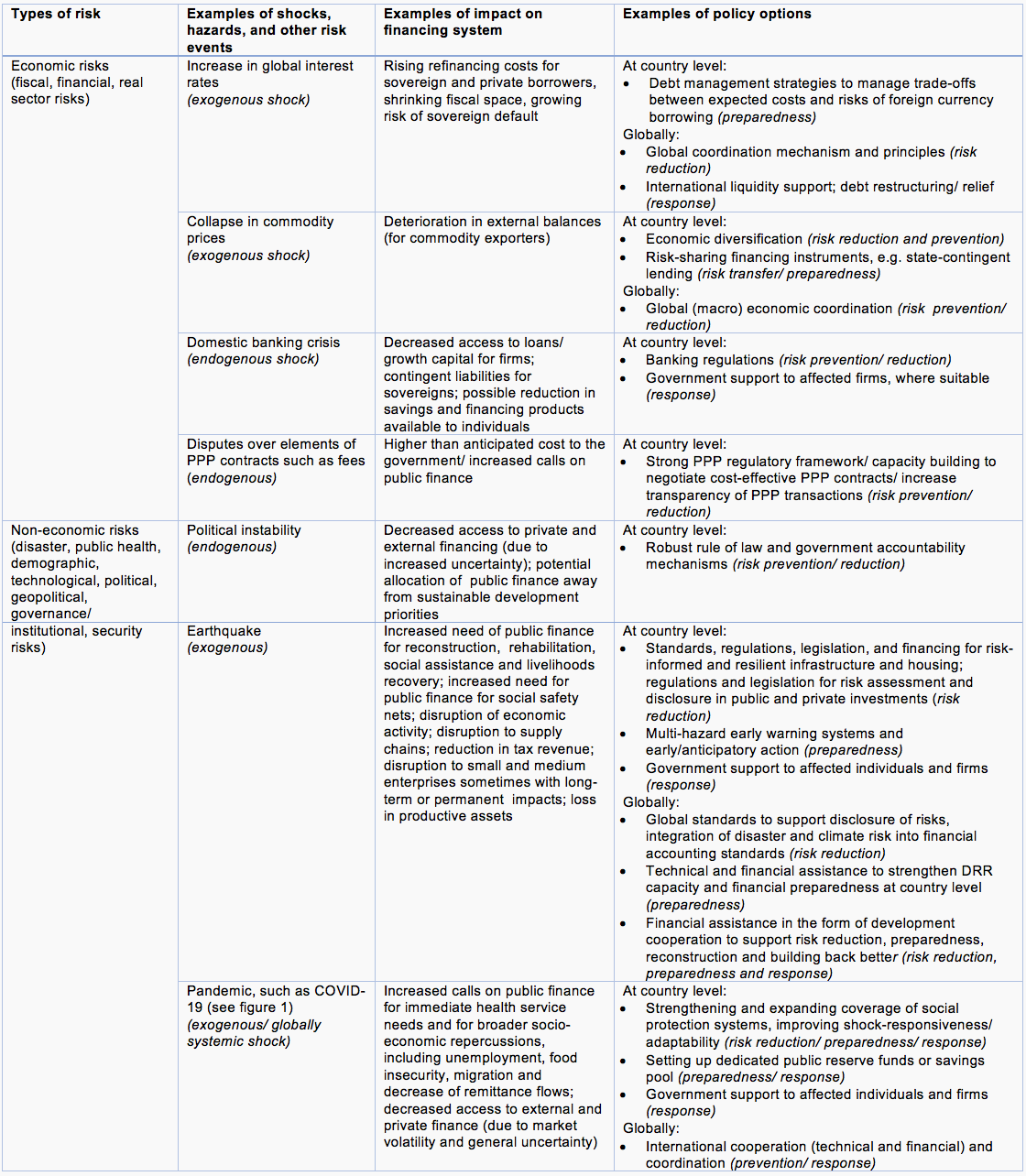

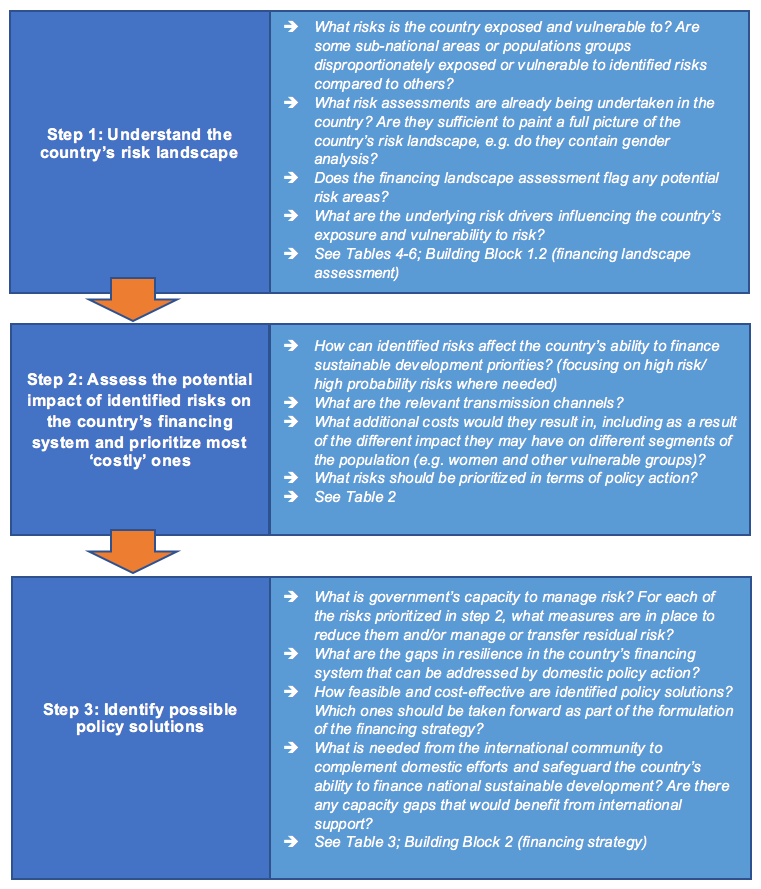

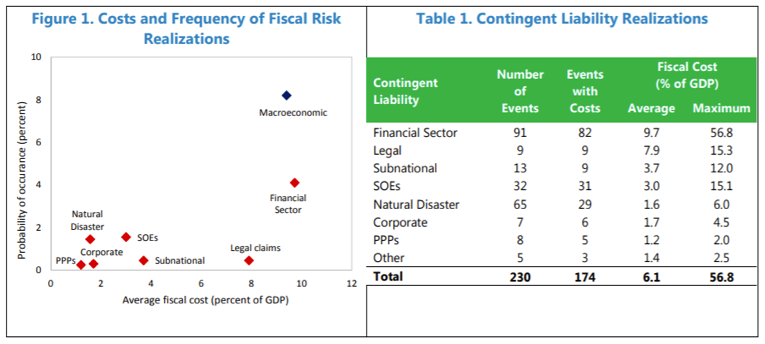

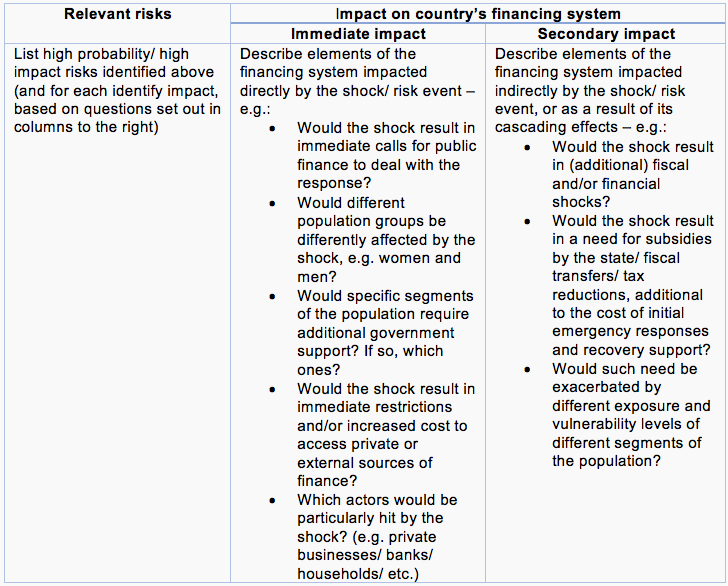

In the context of INFFs, such risk assessments aim to bring a risk-informed perspective to financing policy decision-making, with a view to help policy makers better understand, manage and address risks to a country’s ability to sustainably finance, and ultimately achieve, national development objectives.FN The ‘system at risk’ is made up of the institutions, mechanisms and actors that mobilise, allocate, spend or invest financial resources. They are affected by a range of shocks that cause risks to materialize: economic and non-economic shocks, such as fiscal and financial shocks, climate, environmental, biological and technological (including cyber) hazards (e.g. COVID-19 and the global recession it triggered, or slow onset hazards such as droughts or sea-level riseFN . Risks can also emanate from within the ‘system at risk’, e.g. political and institutional risks, or from specific financing instruments or policy choices.

COVID-19, ecosystem collapse, and the climate crisis also demonstrate the increasing complexity of the risk landscape, with shocks interconnected, cascading effects, and the systemic nature of risks. The accumulation of risk within environmental, social, political, and economic systems threaten countries’ ability to finance sustainable development, and ultimately to achieve the SDGs. Such systemic risks must be part of the INFF risk assessment.

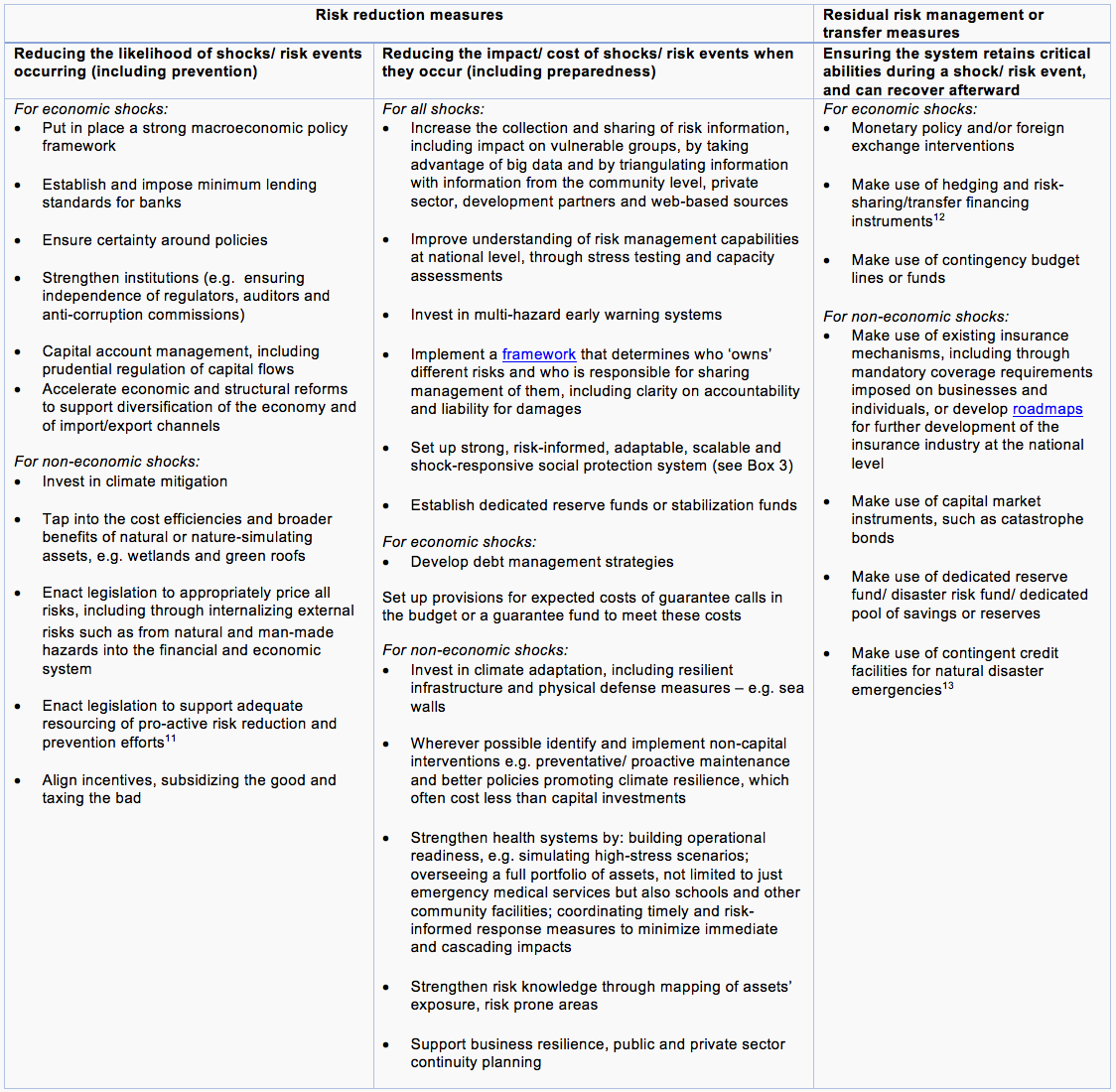

When these risks materialize, they can destabilise part or all of the ‘system at risk’ and have a disproportionate impact on vulnerable people, increasing inequalities. To be sustainable, financing strategies must thus be risk-informed: able to finance the reduction of existing risk, ensure future investments do not create new risk, and providing instruments to cover the remaining residual risk and build resilience. The COVID-19 pandemic may have increased governments’ appetite for developing such strategies, and may help to reverse the tendency of underinvestment in prevention and preparedness.

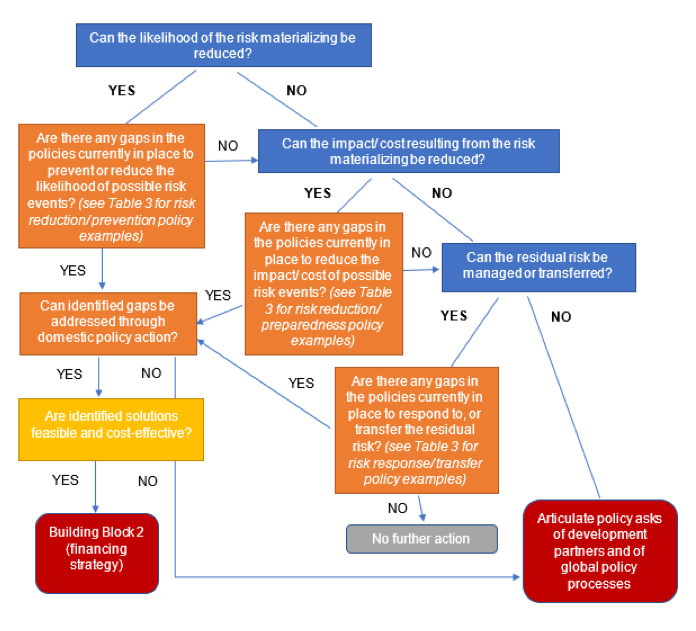

This module presents approaches and tools to assess major risks to sustainable financing, with a view to identify policy actions that can prevent and reduce risk and improve the system’s resilience, including by assessing their feasibility and cost-effectiveness. It should pave the way for a risk-informed and risk-sensitive approach to financing for sustainable development in the context of INFF design and implementation.