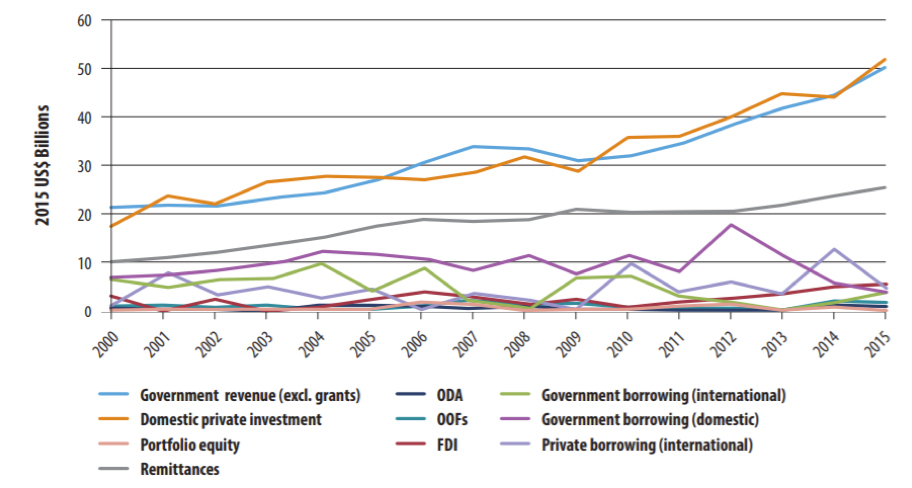

An aggregate look at the financing landscape

can also be helpful to assess the effects of shocks and crises in as

close to real time as is possible, e.g. in the context of the COVID-19

pandemic. High frequency data, where available, can help facilitate real time

analysis and inform crisis policy response and planning for recovery. They

include in-year data on public finance budget changes and spending; remittance

flows, which are often monitored on a monthly basis by the Central Bank; data

from financial markets (such as lending data, exchange rates, sovereign bond

yields, and portfolio investment flows); international bank lending; and some

humanitarian finance flows.

Sustainability

of financing

The sustainability of a country’s fiscal

and external position – including public and external debt sustainability,

access to sufficient foreign exchange to finance vital imports – depends on net

flows over time. Critical stocks (public and external debt stocks, foreign

exchange reserves) and outflows (including capital flight and illicit financial

flows) should also be assessed, in conjunction with a broader risk assessment (see Building

Block 1.3 Risk Assessment guidance).

Reconciling stocks and flows. The fiscal account is routinely reconciled

with key stocks, particularly public debt. Public sector balance sheets could

also be interpreted more broadly to include not just gross public debt, but the

full range of liabilities (including contingent liabilities) as well as public

assets. Such

balance sheets are often poorly understood, due to limited reporting and data

gaps. But they would increase transparency and accountability, reveal risks,

and shed light on hidden liabilities and public sector assets (see Box 2). The latter in particular is relevant in an

SDG context – public investments in the SDGs, e.g. in sustainable

infrastructure and other non-financial assets, create public wealth, increase

public revenue in the long-run, and support sustainable development.

The balance of

payments can be used to reconcile

external financing flows and stock variables to assess the sustainability of

the country’s external position and its external liabilities. Financing

flows captured in balance of payments data, such as direct investment and

portfolio investment in the financial account, debt forgiveness in the capital

account, and aid and remittances in the current account, are also incorporated

in the public and private finance analyses mentioned above. However, looking at

them in their own right provides a useful additional policy-relevant lens of

analysis, able to shed light on potential areas of risk that may otherwise be

neglected (see Building Block 1.3 Risk Assessment guidance).

Illicit flows. Illicit financial flows are not covered in the

flows above. While estimating these is inherently difficult because of their

clandestine nature, there are several ongoing attempts of quantification. The

United Nations Regional Commissions measure components of illicit

financial flows, such as goods-trade misinvoicing. The Task Force

on the Statistical Measurement of Illicit Financial Flows, initiated by UNODC

and UNCTAD in the context of the SDG indicator framework, is field

testing statistical methodologies to underpin estimations of illicit

financial flows at the country level.

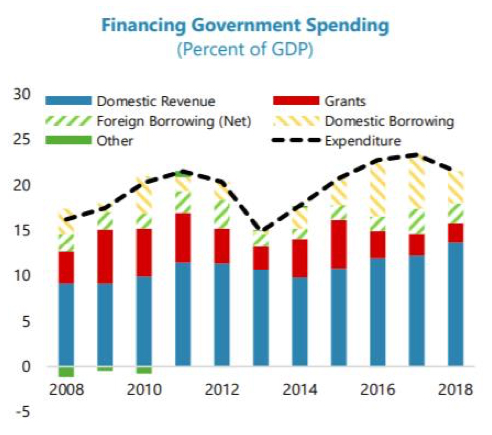

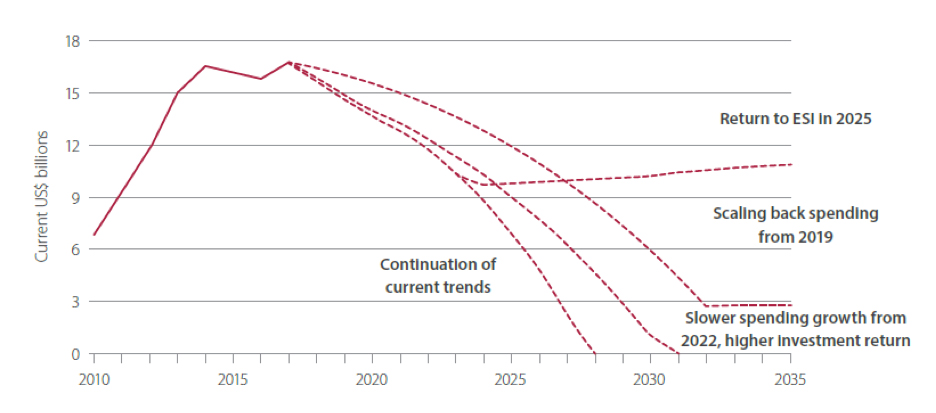

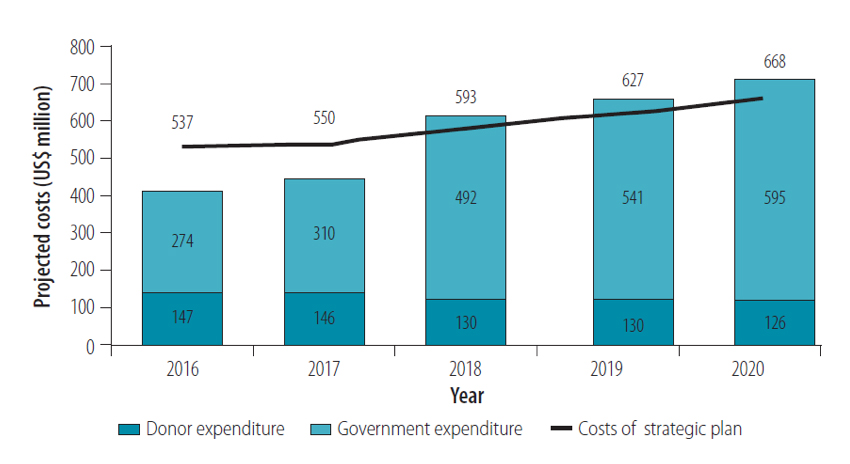

Scenarios and forward-looking trends. Trend analysis can reveal whether critical resources are increasing,

plateauing or declining. Scenarios

and forward-looking trends can help governments determine whether policy

interventions are required. Risks identified in the risk

assessment (see building block 1.3 guidance) should be considered when

assessing such future trends.

The

OECD’s transition finance toolkit (see Table 3) for example helps to anticipate

challenges that arise from growing per capita income levels and related access

to different financing sources. In

Timor-Leste, forward-looking scenarios were used as part of a DFA to assess

potential future trajectories around the country’s Petroleum Fund (Figure 7).

The Fund is a key but finite source of revenue for the government;

forward-looking scenarios supported discussions among policymakers

about investment of its resources, wider options for sustainable

domestic revenue mobilisation and improving the environment for private sector

growth. Additional

examples in step 2 below show how forward-looking trends can also be used to

inform the estimation of financing gaps at the sector level.