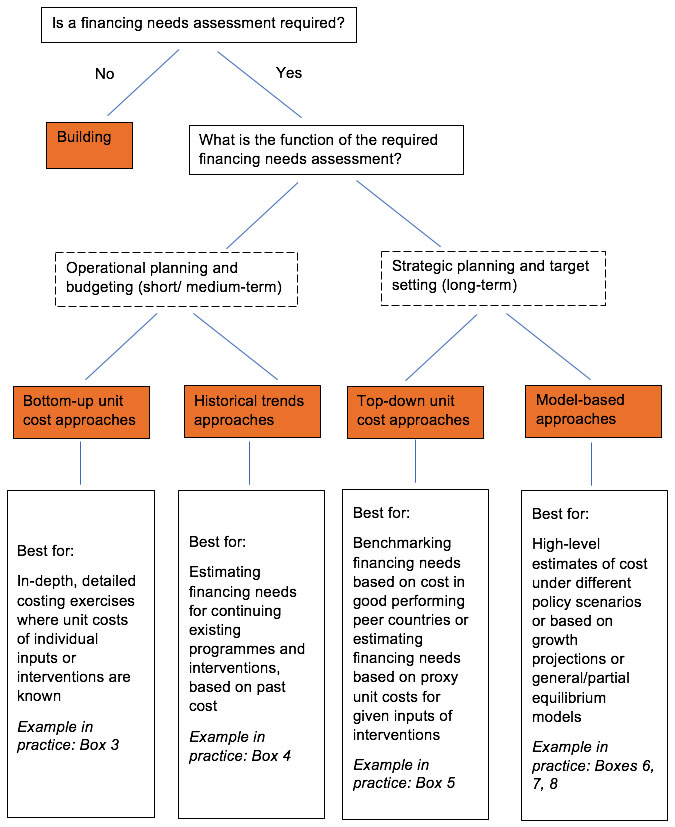

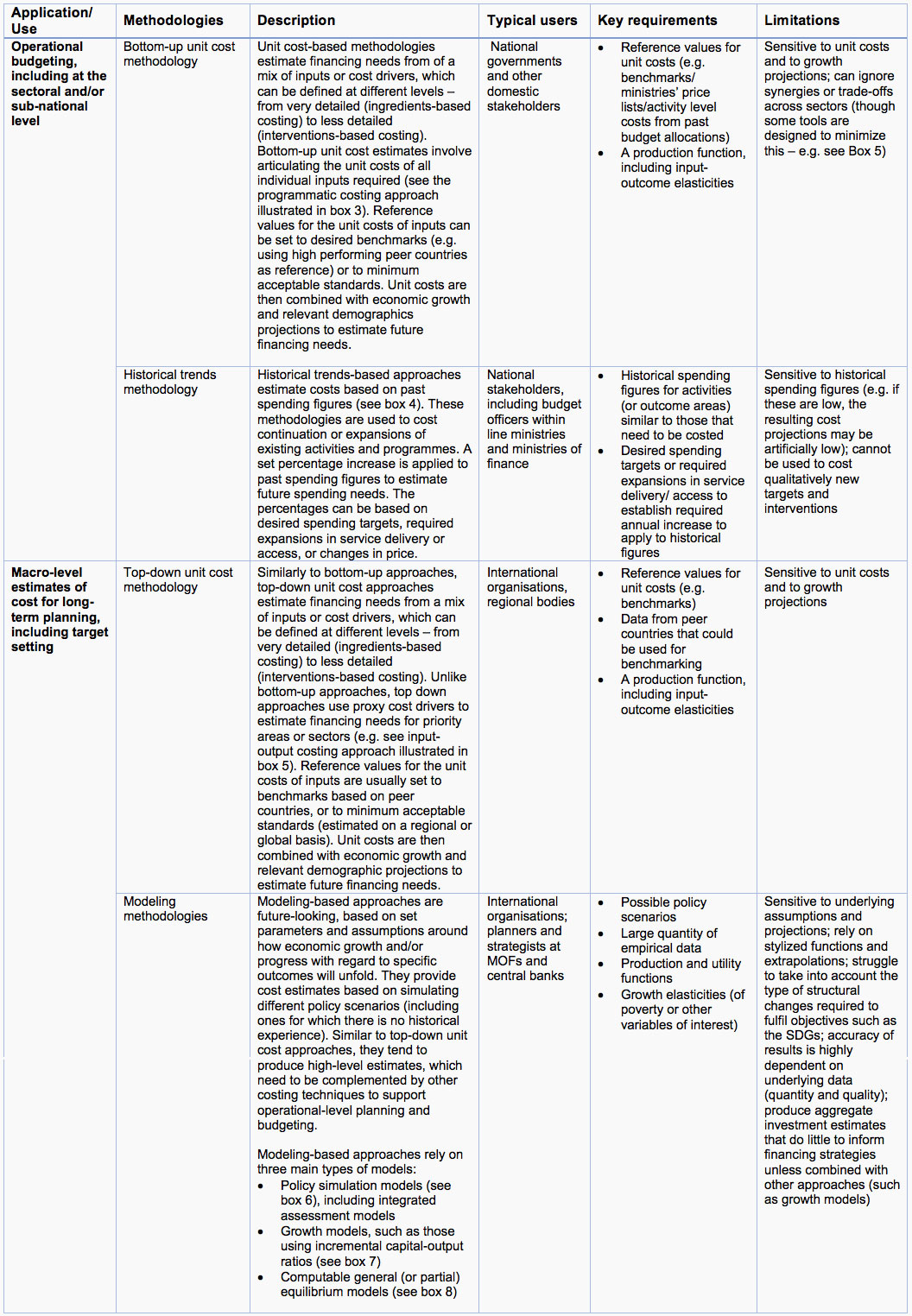

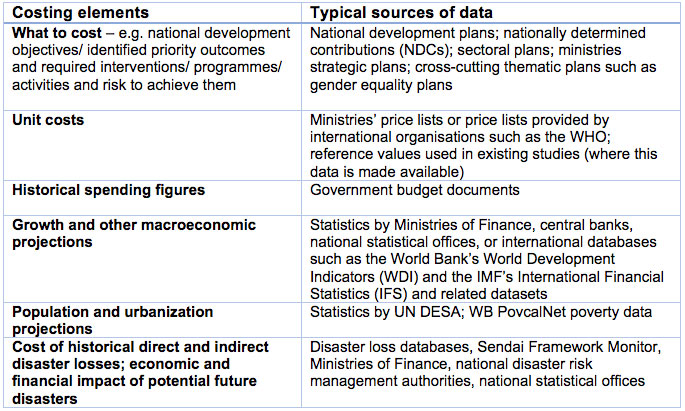

The international community also offers a

multitude of sector-specific costing methodologies and tools. They are grounded

in the basic methodologies set out in Figure 3 and Table 2 but incorporate

sector-specific considerations. Boxes 3, 6 and 8 illustrate examples of some of

these, related to health, energy and land use respectively. A more

comprehensive list is included in Table 4 (see Section 4.3).

Some sectors and thematic priorities are more

easily quantifiable than others. For outcomes where interventions are not standardized

or cross-cutting in nature (such as reduced poverty and inequalities or strengthened

governance and institutions), detailed bottom-up costing approaches may be less

suitable. Top-down or modelling-based costing approaches can provide ball-park

estimation of needs. For example, growth models can be used to estimate economy-wide

investment needs to achieve desired poverty reduction outcomes. Alternatively,

as done in Bangladesh’s SDG financing strategy, costs can be estimated by

determining the financing needed to adequately resource relevant institutions.

For example, to estimate the cost of achieving SDG 10 (reduced inequalities), Bangladesh

identified key ministries whose overall budgets would need to be scaled up to

achieve relevant targets. Similarly, in relation to SDG 16 (peace, justice and

strong institutions), it allocated a lump sum to institutional reform along with recurrent budget allocations to

relevant government agencies and departments such as the police force, prisons

and courts.

The choice of methodology and interpretation of results should also be

mindful of other limitations and challenges:

- Sensitivity to

underlying assumptions: changes to production technologies and the policy and

economic environment, both nationally and globally, cannot be fully known but

may significantly impact costs; similarly, economic and non-economic shocks may

derail growth prospects and thus significantly affect spending needs. Scenario-based

approaches could provide a more robust analysis and facilitate better planning as

well as more efficient and effective financing strategies.

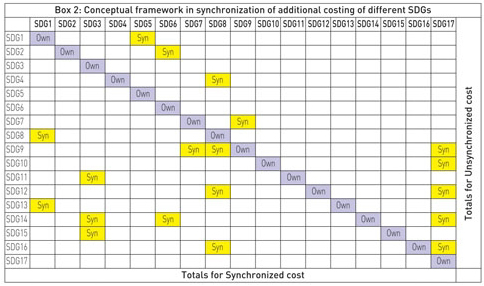

- Synergies and

trade-offs: possible synergies/ co-benefits and trade-offs between different

policy objectives or sectors are not always captured, particularly in bottom-up

and sector-specific exercises, meaning that aggregate estimates of cost can be

inflated.

- Policies and

institutions: costing methodologies are able to account for factors such as

absorptive capacity and spending efficiency only to a limited extent.

- Leaving no one

behind: financing needs assessments may struggle to consider distributional

implications and additional costs to reaching the poorest and most marginalized

people.

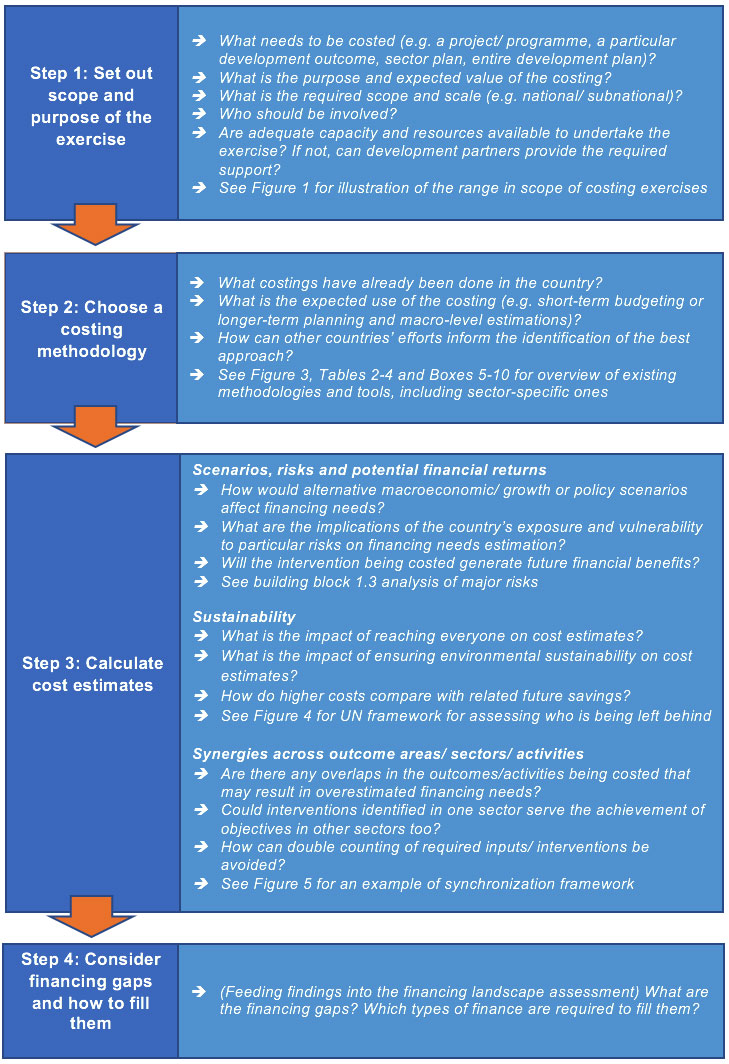

Step 3: Calculating ‘sustainable development-proof’ cost

estimates

While there are inherent limitations to

costing exercises (see above), practitioners have found ways to address them.

They include: considering different scenarios, risks and potential financial

returns to ensure cost estimates are forward-looking; accounting for all

dimensions of sustainability, including environmental aspects and the leaving

no one behind principle; and accounting for synergies across outcome areas,

sectors and activities.

a) Accounting

for different scenarios, risks and potential financial returns

Growth shocks, natural and man-made hazards, and other events outside a

country’s control, such as Covid-19, as well as changes in policy direction or

development priorities can impact cost estimates. Financing needs assessments,

especially those used for long-term planning and target setting, should thus incorporate

scenarios and flexible forward-looking assumptions, e.g. through policy simulation models. Exploring multiple scenarios also allows

for the identification of possible trade-offs between objectives and inform policy

decisions (e.g. see Box 6).

The risk assessments module (see building block 1.3) provides an

overview of the main types of risk that can affect the country’s financing for

development efforts, including their potential financial consequences. This analysis

can inform a balanced perspective on prevention/ preparedness and response

costs. By taking such a risk-informed perspective, INFF costing exercises

strengthen resilience and help minimise the economic (and human) impacts of potential shocks, disasters and

crises. Box 9 illustrates how Nepal’s SDG costing took the country’s proneness to

earthquakes into account.

Some interventions and investments (e.g.

infrastructure investments or investments to protect ecosystems) generate

future financial benefits, be they new/ expanded fiscal revenue streams or future

savings/ avoided costs. Taking these second-round benefits into account avoids

inflating their ‘real’ and long-term cost to the government. Intertemporal balance

sheet analysis can help policy makers build a more holistic picture of the

actual cost of identified interventions.

b) Accounting

for sustainability

The principle of leaving no one behind underpins the SDGs. It should

guide the articulation of interventions and policies and be taken into account

in costing exercises. For example, the poorest and most vulnerable people

are also most likely to be hardest hit by economic shocks and disasters,

impacting recovery costs. Further, it is essential to ensure costing efforts

account for the gender differentiated impacts of particular interventions. Box 9 illustrates

how leaving no one behind was considered in Nepal’s SDG costing exercise.

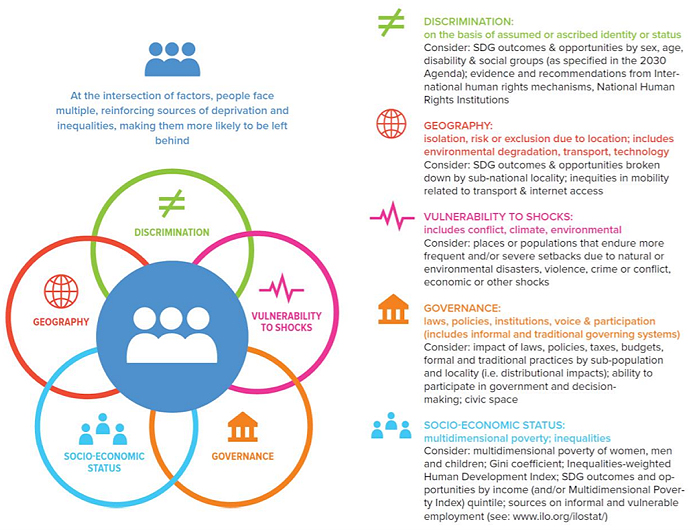

The UN

framework for assessing who is being left behind (illustrated in

Figure 4) may be useful to guide the identification of most-at-risk populations

and to inform revisions to cost estimates accordingly. For example, if

populations living in remote areas are at risk of being left behind, then infrastructure

planning and costing should be adjusted to benefit them.