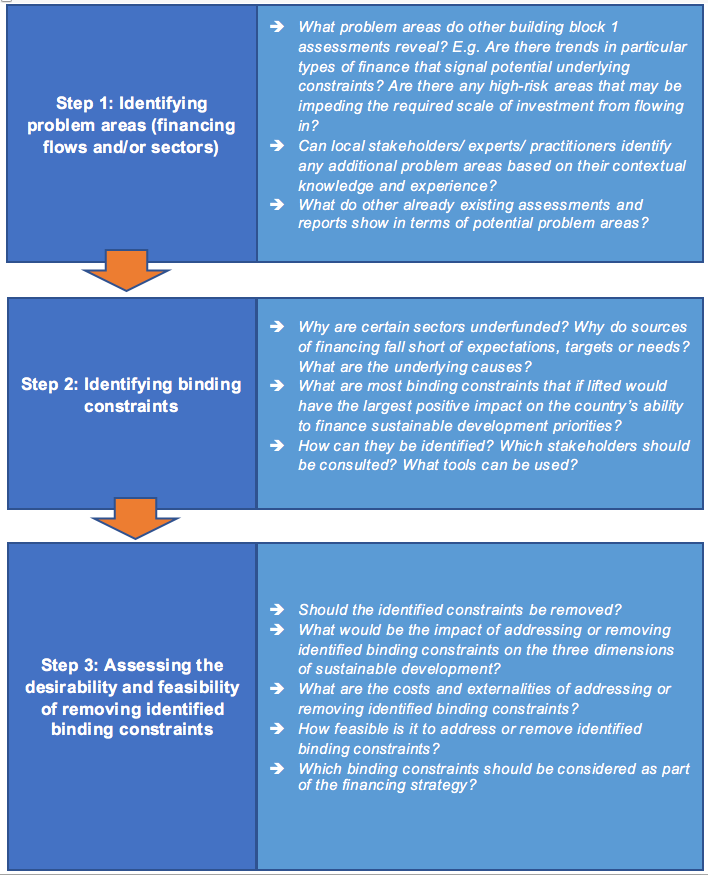

Once problem areas have been identified, the

second step is to ask a series of why questions (e.g. why is

government spending in the education sector below needs? Why are tax revenue

levels low compared to set targets? Why is foreign investment poorly aligned

with national sustainable development priorities? Why do women-owned MSMEs have

lower-than-average access to finance?) and determine the major underlying

causes, or in other words, the most binding constraints.

A structured series of dialogues and inquiry, following steps a) through

e) laid out below, assesses each of the problem areas identified in Step 1 by asking

questions, and gathering relevant evidence and perspectives from stakeholders

to facilitate the identification of related binding constraints (Sections 4.2.1

and 4.2.2 provide examples of its application in both public and private

finance problem areas). The problem areas identified in Step 1 will determine the

experts and practitioners that should be consulted, as well as the most

suitable tools and sources of data and evidence. For example, if problem areas

are identified in particular sectors (e.g. health/ education/ agriculture/

housing/ etc.), relevant sector-specific expertise and knowledge will have to

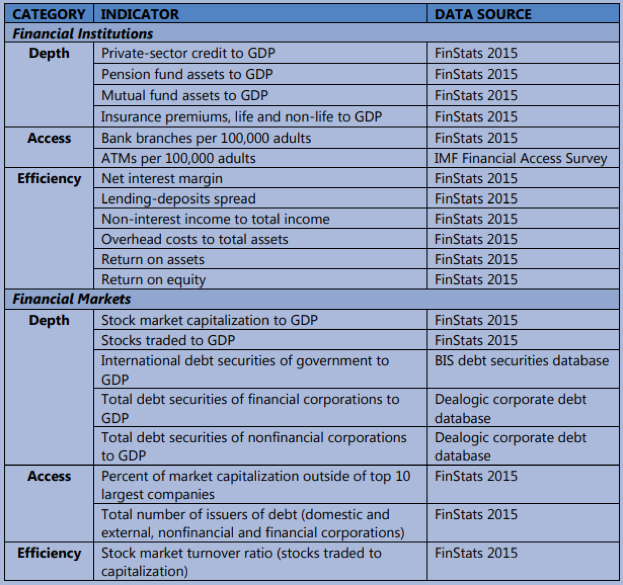

be sought. Section 4.4 lists tools and assessments available from the international

community that countries can draw upon to complement local knowledge and expertise;

they range from public financial management and investment assessment tools to

private sector diagnostics, productive capacity and financial sector

assessments.

a) Turn the problem area into a

‘why’ question to guide the exercise. For example,

why is tax revenue below target levels? Why is domestic private investment

lower than in peer economies? The set of plausible answers become the branches

of a ‘decision-tree’ to further explore.

b) Explore and map possible

answers to the ‘why’ question. By drawing on local

knowledge and evidence from existing assessments (such as those listed in Section

4.4), possible reasons that may explain the problem area can be mapped, all the

way down to the fundamental underlying causes, or in other words, the possible binding

constraints. All possible types of

binding constraints should be considered, including market-related,

institutional, policy and/or capacity-related constraints. It is critical at

this stage to involve the right stakeholders (relevant government and non-state

actors who can provide concrete insight from the implementation level) so that

no potential binding constraint is left out of the short-list, including ones

that may be particularly relevant to specific segments of the population.

c) Formulate a binding

constraint hypothesis. One of the short-listed

binding constraints is posited as a primary underlying cause of the problem.

d) Test the hypothesis. The identification of binding constraints is often a matter of

judgement and not precise science, and thus relies on insights from local

experts and specialists. Nonetheless, constraints that are truly binding should

exhibit certain properties that

can guide hypothesis testing. Quantitative analysis, where appropriate, and

consultations with practitioners and institutional stakeholders can shed light

on whether certain constraints are indeed binding in the specific

national context:

i. Would increased supply of a constrained

input have a large impact on the ‘objective function’, e.g. the price or cost

of the objective? The constraint has a high

price/ “shadow price”. While “shadow prices” are not always observable, they can be signalled by

market prices. For example, high real interest rates can signal that access to

finance is scarce and potentially a binding constraint.

ii. Would removal of the

constraint provoke a major positive impact in the problem area? Changes in the constraint would produce shifts in costs, incentives

and behaviour. For example, service delivery providers in the public sector

(e.g. in health or education) may be able to pinpoint those aspects of public

financial management that most adversely affect them. If access to finance is the

most binding constraint to domestic private investment, increased availability

of credit would significantly increase investment.

iii. Do agents affected by the

problem attempt to bypass or overcome the constraint? There is inefficient or costly economic behaviour in the problem

areas. Agents often find alternatives to circumvent constraints, such as barter

during hyperinflation or borrowing at high interest rates in the informal

sector due to banks’ high collateral requirements.

iv. Do individuals, firms and

institutions less reliant on the constraint perform better than others? Those not as impacted by the constraint are more likely to survive

and thrive, and vice-versa. For example, in the case of access to finance being

posited as a binding constraint to domestic private investment, firms in

sectors that are more likely to be able to self-finance investments will be

performing better than those that depend on debt and external financing.

e) Repeat c) and d) until the

right binding constraint is identified. If the

binding constraint posited in step c) is found not to meet properties listed in

step d), an alternative hypothesis is formulated and tested until the right binding

constraint related to the specific problem area is identified.

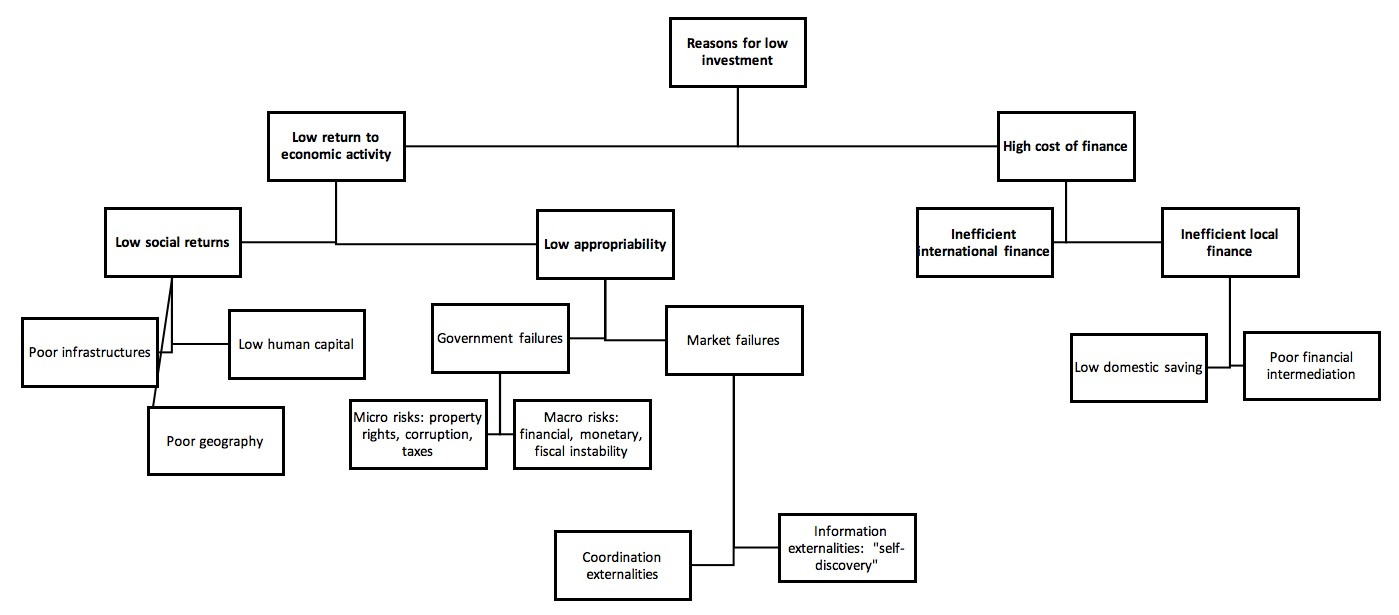

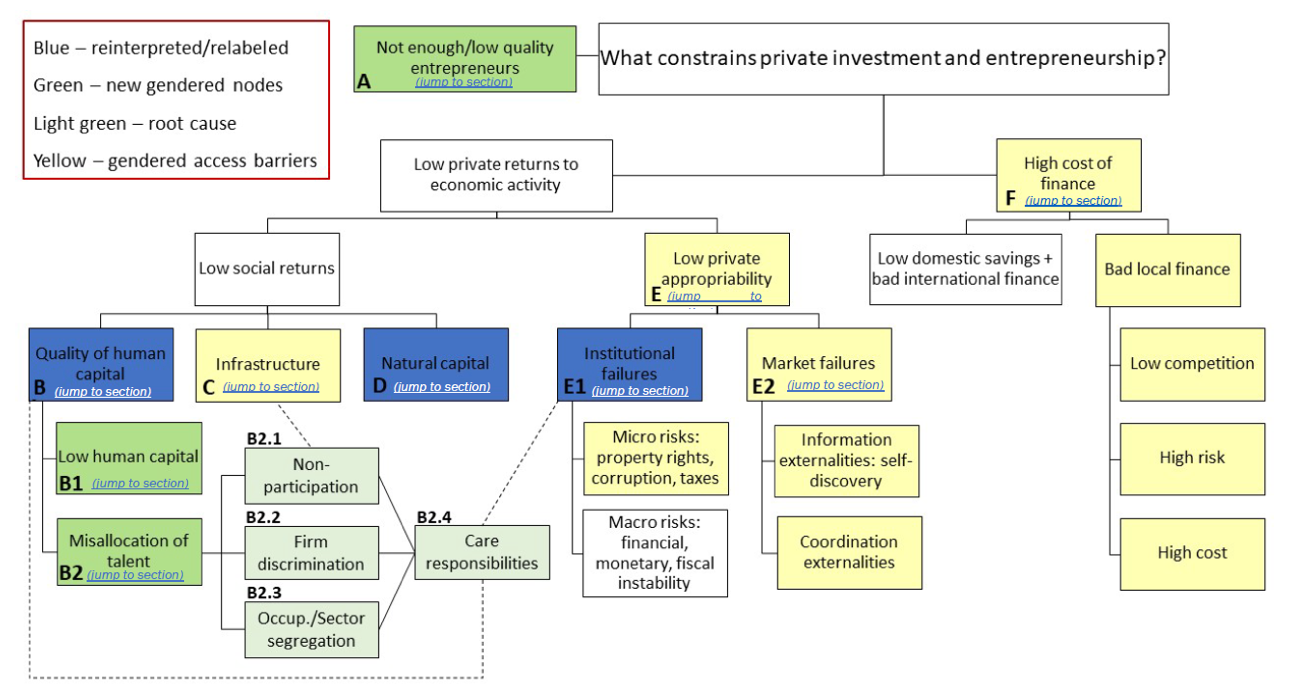

The approach is inspired by the

‘growth diagnostic’ methodology, which at its core seeks to identify a

small set of key obstacles to economic growth relevant to the specific national

context (instead of following international ‘best practice’ or ‘cookie-cutter’

approaches), and to strategically focus efforts and limited capacities and

resources (or ‘political capital’) for policy change and reform. INFFs are

broader in ambition. All dimensions of sustainable development come into play,

and constraints beyond those that may be unearthed using a growth diagnostic

are also relevant (e.g. public financial management and state capacity issues).

As such, the approach outlined here borrows the problem-driven, decision-tree

method of growth diagnostics but applies it to the broader objective of INFFs.

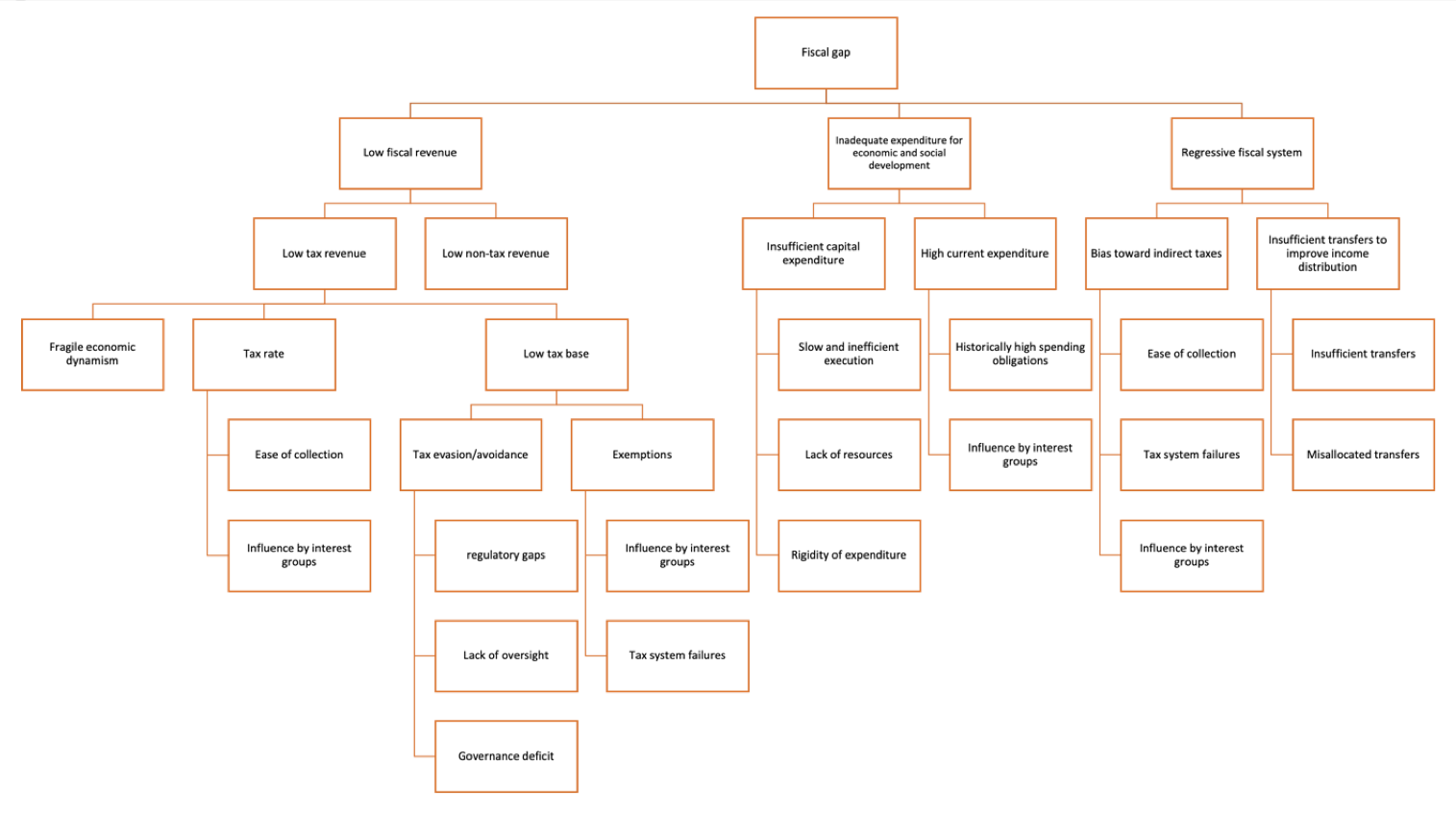

4.2.1. Applying the approach to public finance

An illustration of how the approach may be

applied to a public finance related problem area is provided in Figure 2. In

2016, the government of Costa Rica, with technical support from the UN Economic

Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), assessed the structural

economic, social and institutional gaps of Costa Rica. The report

drew attention to institutional and capacity gaps in the tax system that

explained its ‘fiscal gap’, or, in other words, the structural challenges in

its fiscal system to manage resource mobilization and public spending to

support sustainable and inclusive development. A decision tree was developed to

assess binding constraints, mapping three potential drivers of the fiscal gap:

low fiscal revenue, inadequate expenditure for social and economic development,

and a regressive fiscal system. The analysis concluded that low tax revenue was

the main reason behind Costa Rica’s fiscal gap, and that the most binding

constraint underlying such low levels of tax revenue were low income and sales

tax revenues, as a result in part of high levels of tax avoidance and evasion

(see Figure 2).